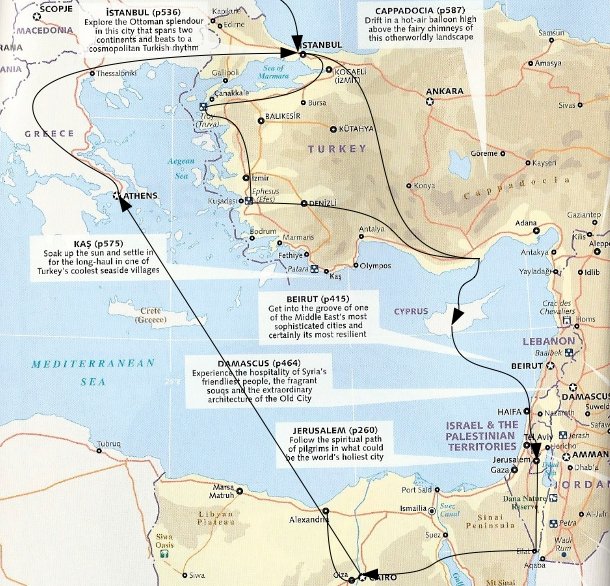

We find our heroes wandering about Turkey, in search of a cute coffeeshop and some decent vegeteryan food. We’ve now visited the phallic formations of Cappadocia, the whirling religionates of Konya, the mineralogical metropolis of Ephesus, and the seaside settlement of Ayvalik. As we turn homeward for a plane from Istanbul to Cairo, we remember fondly some of our best Turkish moments.

After scrambling over the hollow mountains of Goreme’s Open Air Museum, filled with 8th century fresco masterpieces and 10th century cave scribbles, we decided to visit one last cave-church. After trying the cave’s bolted door, we found the attendant, his dog, and his stovedrum boiling tea. The price, he said, was 8 lira, per person. We shrugged at his one mountain (we had just seen twelve such for 15 lira), and started to walk away. “Okay!”, he called, “For you, special deal– 8 lira for both.” We accepted, and he led us into the cave and explained the dilapidated frescoes. Could we take a picture? “Normally, no. Well, okay. You argue well.” As we were leaving afterward joining him for a cup of tea, he said, “You want to come back tomorrow? I show you The Secret Church, hidden. Special for you.”

In Konya, we were confused by the dedicated pilgrims at the former home of the whirling dervishes. Their mosque is packed with the trappings of dozens of these dancing scholars, but since when do performing artists get centuries of devotion? We didn’t think to wonder why the site is called the Mevlana Museum, until we sat for tea at a hotel (which had great food, which we had scoffed at earlier in the evening, when we were set on finding another restaurant and ended up a t a ghetto fast-food joint). They gave us a nifty pamphlet for the hotel since Flame wanted to know the Turkish names of every food. The pamphlet gave a brief history of Mr. Mevlana, father of a more open, accepting form of Islam. We could have learned something from him a few times that day.

We met a nice Brit, Ed, in Selçuk, who kept Flame company as I got lost among some forbidden ruins. As we were parting ways at the bus station, a bus agent approached him and asked him where he was going. “Pammukale,” said he. “Why don’t you give your bag– this is your bus!” the agent said. Ed protested: the sign in the bus window had it bound for a town on the way to Pammukale, but he had gotten a direct ticket. The agent stepped away and talked to the driver, who reached under his dashboard and pulled out a “Pammukale” sign and stuck it to the window under the other one.

For our bus from Selçuk to the Greek cobblestone maze called Ayvalik, we were first offered a price of 65 lira. A novice bargainer, but suspecting a gringo tax, I offered 60. The agent got on the phone, and after a long talk said that, seeing as it was the first of the year, he could make me a special offer: 55 lira. Okay, so I handed over a 50 lira note and a 10 lira note, and rather than give me change he took the 50 note and said, “That’s enough.” By now we realized we were paying way too much, but it wasn’t until the larger bus depot at İzmir that we realized how much. The driver walked us to the bus for the rest of our journey, where we got a new ticket: it said it cost 27 lira. And the bill that Flame saw the driver palm over for the ticket was a 20.

We just arrived in crazy Cairo, where the midnight sounds of honks and Arabian music echo all around us. The streets are a deathwish, which we’ve already braved more times than we ever want to remember, but tomorrow is a whole new day!