I started taking a spiritual growth class in DC, under the auspices of the Baha’i community. There are a progression of books developed by the Ruhi Institute in Columbia and now used all over the world, and covering topics from the role of service to the nature of life and death. The sections we’ve done so far border on inanity (worksheets with true/false questions, fill in the blanks), but the participants are smart, and open, and mostly of non-semetic Middle-Eastern descent (of which I have practically no other friends), so I’m enjoying it.

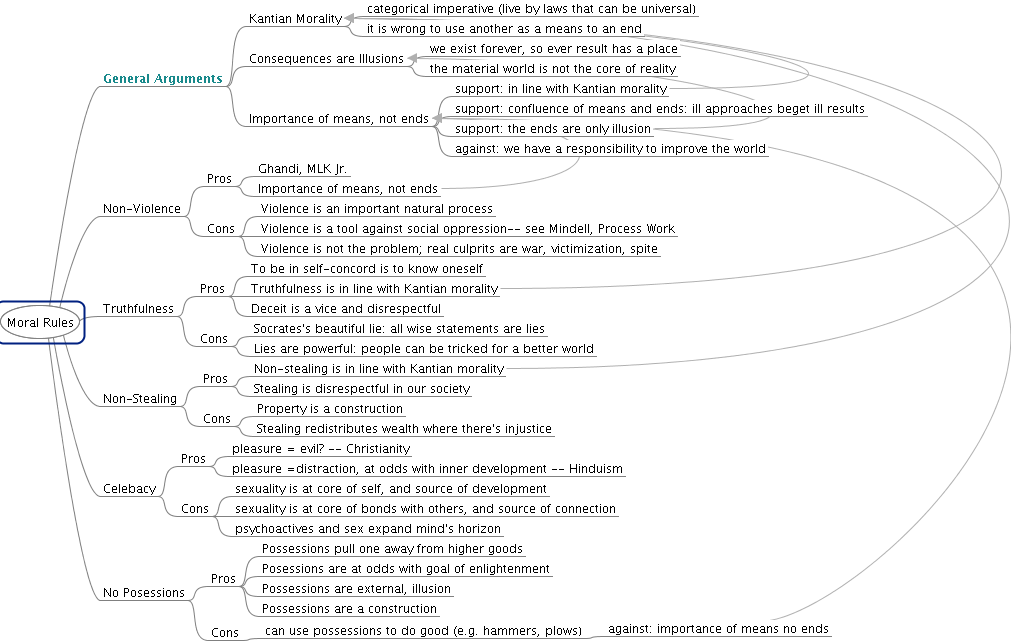

At the last meeting, someone mentioned having difficulty with the “rules” of Baha’i, and since no one ever told me it had any rules, I tried to get a list. None was forthcoming, but a few emerged over the course of the discussion. I didn’t really agree with them, but rules aren’t one of the ways I organize my life, so what do I know? My recently-beloved book on Philosophies of India (Heinrich Zimmer) has also been throwing rules around, as parts of philosophies I otherwise adore. So I want to figure them out: Does the virtuous life have rules?

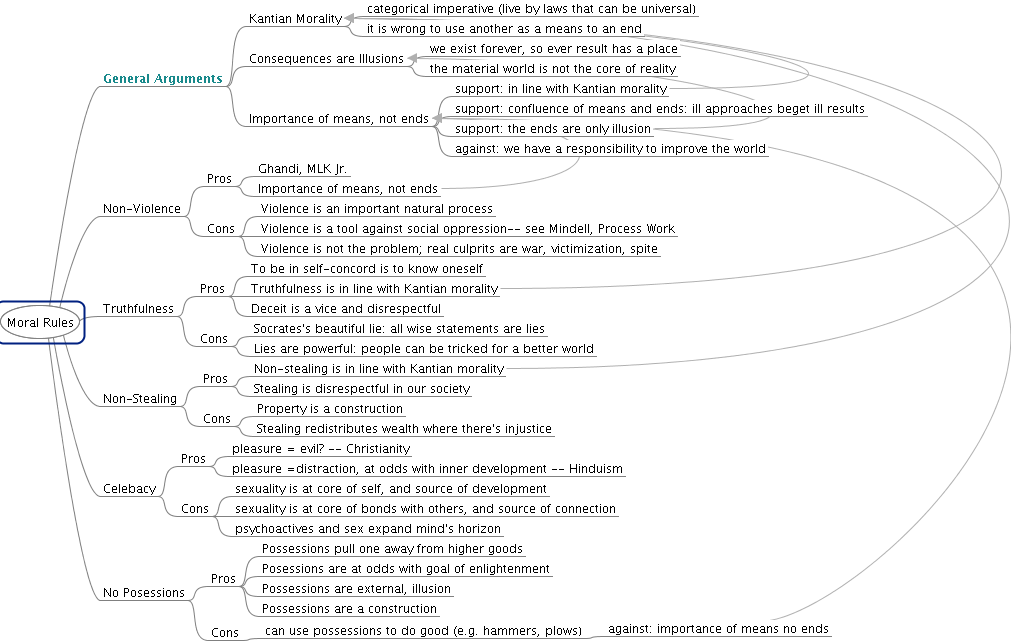

Here are the five recurring big ones, as present in the Vedanta (excerpted from Zimmer, 433-434):

* ahimsa, non-violence: “renunciation of intent to injure other beings by thought, word, or deed”

* satya, truthfulness, honesty, sincerity: “the maintenance of identity between thought, word, and deed”

* asteya, non-stealing

* brahmacarya, a life of celibacy (in Baha’i, it’s non-inbibing and non-sex-outside-marriage)

* aparigraha, non-acceptance, rejection, renunciation of all possessions

I recognize the virtue in each one and have objections to each one, and I don’t know how to work those out or balance them (Is a rule balanced with exceptions still a rule?). Like a court case, I want to lay out some of the arguments, for judge and jury to better decide.

Hinduism recognizes that different rules apply to different stages of life. According to them, I shouldn’t be celibate or possessionless until I’m 50, when it’s an appropriate time to focus on my enlightenment. So, these aren’t my arguments for everyone, everywhen; they’re firstly for me, now.

Spiritual rules are a fascinating concept. Flame’s Judaism has 613 mitzvahs, which act like a comprehensive buffet of good deeds writ as lifestyle commitments. Each is seen simultaneously as restriction and source of spiritual strength. My parents’ Lutheranism has only guidelines and no hard rules– spiritual progress is by personal redemption– and yet seems no less committed to good works. Unlike Judaism, I don’t believe that adhering to rules is a virtue in itself. Rather, rules are practices or meditations which lead to virtues, like the ancient Hindu mandatory sacrifices which didn’t themselves pave a road to enlightenment, but helped conform the mind and soul progressively closer to the gods. Conversely, the wrong rules, however inherently virtuous their prescribed actions might be, can contort the soul ugly ways, like extreme austerities that engender pride and hate. Nor are spiritual rules like the moral “rules of thumb” meant to facilitate Utilitarianism. The spiritual law is a kind of contract, entered into by profound life decision, and broken only at a doubled moral peril. Who notarizes the contracts, and builds the bridges between the practice and the virtue, are important questions.

I also have some odds with the normal motivations behind engaging in spiritual rule. I’ve realized that I want neither disassociated enlightenment, nor specific connection to any god. Where Hinduism tries to stave off distraction, I want to be immersed in it, but I want to encounter it as signal rather than noise. I want to live a life in awe of the world, not outside it. Where Jainism wants to distance, I want to engage, and have the wisdom to know when and how to interfere.

Here are my arguments for and against each of the rules. What did I miss?