Maybe questions of social science never get truly resolved. The first year of my PhD, I remember John Mutter describing the question of creative destruction. Sometimes, the story goes, a disaster can lead to an unexpected silver lining. By destroying outdated infrastructure, or motiving people to work together, or driving a needed influx of aid, a disaster can eventually leave a community better off than beforehand. Mutter described it almost like a philosophical quandary. In the face of all the specifics of institutions, internal perceptions, and international relations, how will we ever know?

For years now, Solomon Hsiang has been producing insights from his LICRICE model, turning hurricanes into exogenous predictors. As these random shocks echo through societies, he’s been picking up everything that falls out. I got to listen to some of it when news reporters would call his office. His work with Jesse Anttila-Hughes turned up the true mortality threat of disasters, typically 10x the lives lost at the time of the event. Jesse dug further, finding how family assets changed, how meals were redistributed, and how young girls are often the most hurt, even those born after the disaster.

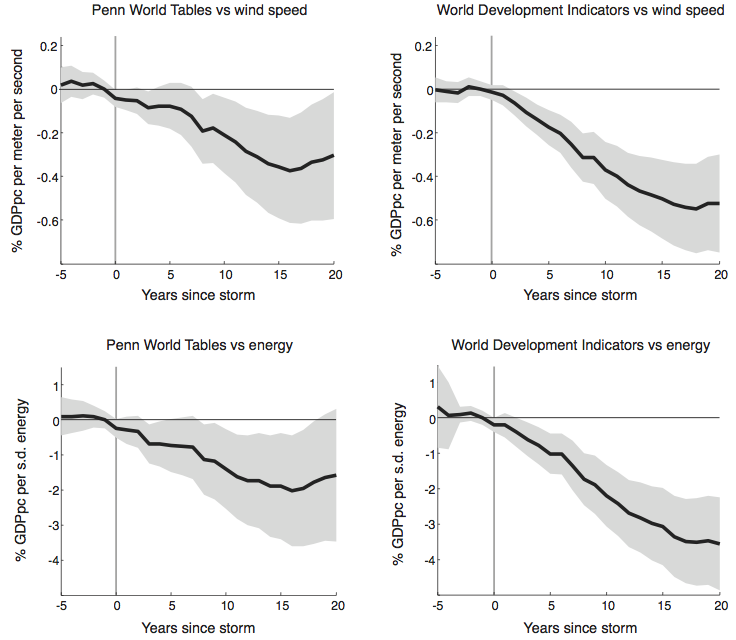

Last month, Sol and Amir Jina produced an NBER working paper that steps back from the individual lives affected. Their result is that a single storm produces losses that continue to accumulate for 20 years. People are not only continuing to feel the effects of a hurricane 20 years down the road, but they additional poverty they feel at 10 years is only half of the poverty that they’ll feel in another 10.

Of course, this is an average effect, and an average of 6415 different country results. But that means that for every country that experiences no long-term effect, one experiences twice the poverty.

So, is there creative destruction? It’s very, very unlikely. The most likely situation is “no recovery”: countries will never return to the trend that they were on prior to the event. Things are even more dire under climate change,

For a sense of scale, our estimates suggest that under the “Business as usual” scenario (with a 5% discount rate) the [present discounted value] of lost long-run growth is $855 billion for the United States (5.9% of current GDP), $299 billion for the Philippines (83.3% of current GDP), $1 trillion for South Korea (73% of current GDP), $1.4 trillion for China (12.6% of current GDP), and $4.5 trillion for Japan (101.5% of current GDP).

That’s what we should be willing to pay to avoid these costs. In comparison to the $9.7 trillion that just additional hurricanes are expected to cost, the $2 trillion that Nordhaus (2008) estimates for the cost of a climate policy seems trivial. That’s two big, seemingly unanswerable questions as settled as things get in social science.