Dividing an elephant in half does not make two small elephants. It makes one mess.

The same is true of our oceans. Modern management of the natural environment is all about dividing up elephants, assigning the halves to different owners, and blinding ourselves to the activities beyond our halves. But just as with elephants, pieces of an ocean depend on each other: fish and currents do not respect national boundaries.

That is the starting point of a new paper Nandini Ramesh, Kimberly Oremus, and I recently published in Science, entitled “The small world of global marine fisheries: The cross-boundary consequences of larval dispersal“. We wanted to understand how national fisheries depended upon each other.

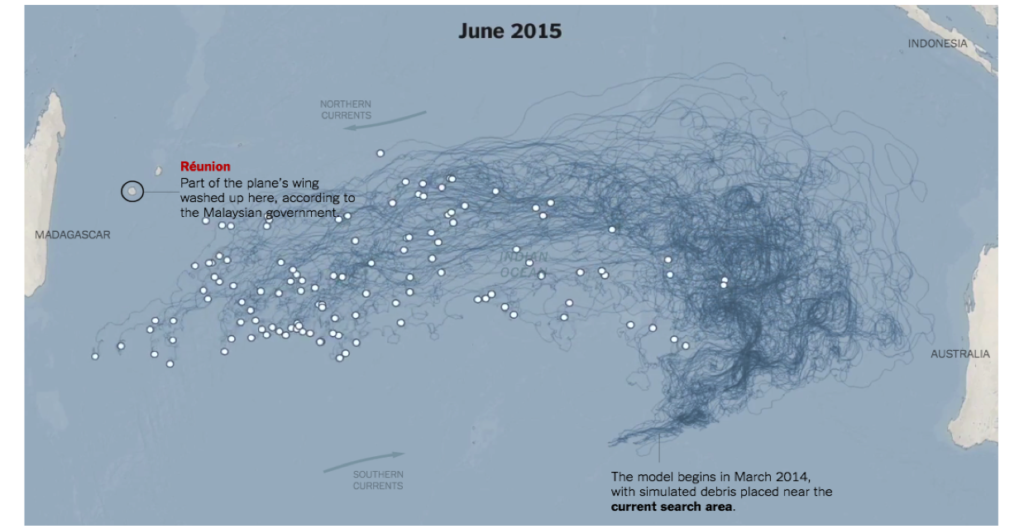

To study this, we used the same model used to study how debris from the Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 crash ended up halfway around the world:

Instead of looking at airplane debris, we looked at fish spawn. Most marine species spend a stage of their lives as plankton, either in the form of floating eggs or microscopic larvae. They can travel huge distances as they float with the currents, sometimes over the course of several months. We can use those journeys to identify the original spawning grounds of the adult fish that are eventually caught.

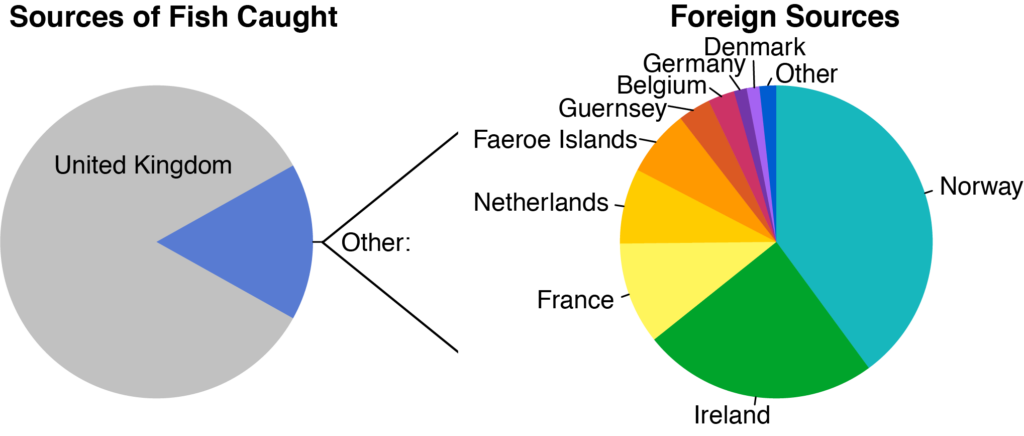

These connections are important, because they mean that your national fisheries depend upon neighboring countries. Spawning regions are highly sensitive, and if your national neighbors fail to protect them, the fish in your country can disappear. A country like the UK depends upon plenty of other countries for its many species.

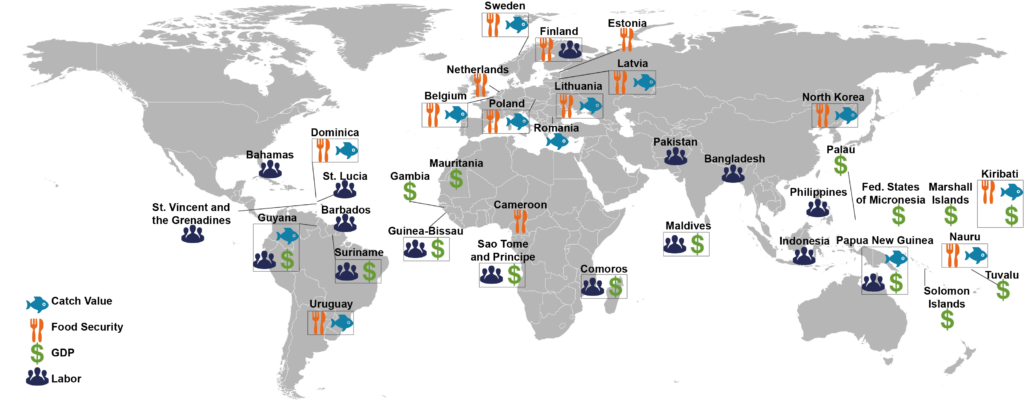

Finally, this is not just an issue for the fishing sector. We also looked at food security and jobs. People around the world depend on the careful environmental management of their neighbors, and it is time we recognized this elephant as a whole.